In recent years, the question ‘Were there black Vikings?’ has sparked considerable debate among historians, archaeologists, and the general public. This fascination reflects a broader curiosity about the historical and cultural dynamics of Viking societies, pushing scholars to re-examine ancient texts, artifacts, and genetic evidence.

Amidst this growing interest, researchers have delved into a variety of sources, from rune-inscribed stones to the very DNA of ancient Norsemen, aiming to paint a clearer picture of their societal structure and external affiliations. This academic pursuit not only bridges the past with the present but also underscores the evolving nature of historical narratives, inviting a more inclusive examination of the Viking Age that transcends traditional boundaries.

Viking Voyages and Cultural Exchanges

The Vikings, originating from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, are widely known for their extensive voyages across the sea from the late 8th to the early 11th centuries. Their expeditions took them across diverse landscapes, from the remote shores of North America to the Mediterranean.

As skilled sailors, traders, and raiders, the Vikings developed an intricate network of routes. This network was more than a means for raiding distant territories; it facilitated the exchange of goods, cultures, and ideas, linking them with diverse peoples and civilizations, each with its own unique traits and appearances.

In their journeys to the Mediterranean and the Middle East, the Vikings encountered other Caucasians and Arabs—peoples with olive to light brown skin, who looked significantly different from the Sub-Saharan Africans.

The expeditions brought them into contact with many cultures, such as the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, and notably, Miklagard—or Constantinople as it is known today. While in the Iberian Peninsula and Italy, the Vikings engaged in both plunder and trade, but it was in Miklagard that the Vikings’ role expanded beyond that of mere traders and raiders to include mercenaries.

The Varangian Guard and Miklagard

Miklagard was renowned for its great wealth and strategic significance which attracted Vikings not only for plunder but also for the opportunities it presented. The city served as a major trading hub where Vikings could sell their goods, including slaves and furs, and in return, acquire luxury items not found in Scandinavia.

Moreover, the Varangian Guard, an elite unit of the Byzantine Emperor’s personal guard, was famously composed of Norsemen, highlighting the depth of their integration into one of the era’s most sophisticated societies.

Despite these connections in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, there is a clear distinction between these people and the Sub-Saharan Africans. The darker skin tones were beyond the Vikings’ geographical and cultural reach during this era. And even if there were blacks sold as slaves in Miklagard, there is no evidence that the Vikings bought, hired, or befriended them to be part of their society.

Genetic Evidence

Recent advancements in genetic testing, including those accessible through home gene testing kits, have revolutionized our understanding of historical populations, offering direct insights into the ethnic compositions of our ancestors.

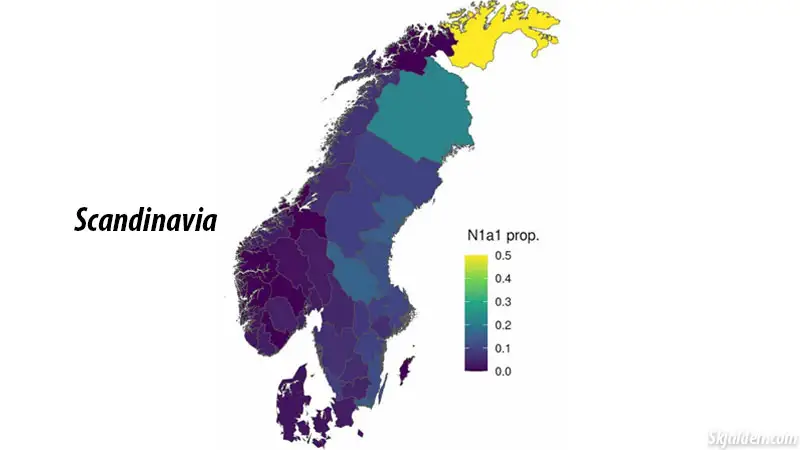

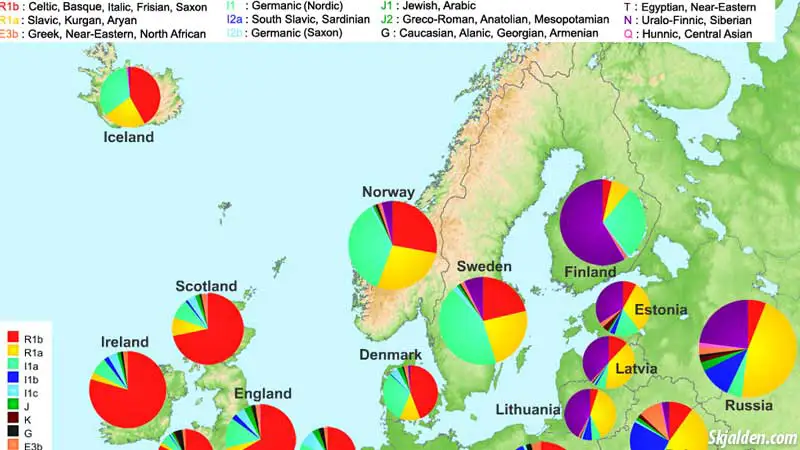

Specifically, studies employing modern genetic testing and osteological analysis have provided crucial evidence regarding the ethnic makeup of Viking populations. Contrary to the speculative narratives of “black Vikings,” these scientific inquiries have found no evidence of Sub-Saharan African ancestry among the Vikings.

This absence of Sub-Saharan African genes in Viking populations not only corroborates historical narratives and linguistic analyses but also challenges modern misconceptions about the racial diversity of these ancient societies.

The integration of home gene testing technologies into the public domain has given people widespread access to genetic information, allowing individuals to explore their own ancestral backgrounds and contributing to a broader understanding of our collective past.

Exploring our genetic roots really shows the difference between what’s often believed and what science actually tells us. It proves how crucial it is to rely on real evidence when we talk about history.

Archaeological Evidence

Despite the widespread fascination with Vikings and their extensive voyages, archaeological evidence has yet to substantiate the presence of Sub-Saharan Africans within Norse societies during the Viking Age. Excavations of Viking burial sites, settlements, and places of gathering across Scandinavia and their known areas of activity have provided invaluable insights into the lives, cultures, and movements of these peoples. These findings include a wealth of artifacts such as weapons, jewelry, ships, and tools that reflect the aesthetic values, technological capabilities, and social structures of Viking societies.

Notably, the analysis of these materials has not revealed artifacts that can be directly linked to Sub-Saharan African origins or influences. Unlike in the Mediterranean, where archaeological finds sometimes reflect a confluence of cultures due to trade and conquest, Viking artifacts maintain a distinct Norse character without indications of African integration.

This includes the absence of African iconography or stylistic influences in Norse art and material culture, which would likely be present if there had been significant interaction between Vikings and Sub-Saharan Africans.

Furthermore, the skeletal remains excavated from Viking Age burial sites have been subjected to detailed osteological analysis. These studies aim to understand the health, lifestyle, and, where possible, the genetic ancestries of the individuals.

To date, such analyses have not identified any individuals with anatomical features that would suggest Sub-Saharan African descent. This aligns with the genetic evidence, reinforcing the conclusion that there was minimal to no direct contact between Viking societies and Sub-Saharan African populations.

The lack of archaeological evidence supporting the presence of Sub-Saharan Africans in Viking societies further strengthens the argument made by genetic studies. Together, these lines of inquiry provide a comprehensive view of the ethnic and cultural composition of Viking Age Scandinavia, suggesting that interactions with Sub-Saharan Africans, if they occurred at all, left no significant imprint on the archaeological record of the Viking era.

Linguistic Insights

The myth of “black Vikings” arises from a combination of misinterpretations of historical texts, and artifacts, and a modern desire to reimagine the past in a way that reflects contemporary values and understandings of diversity.

Historical, linguistic, and cultural analyses reveal that references to “black” in Norse sagas and other medieval Scandinavian texts typically pertain to hair color or, in some instances, a darker complexion relative to the typical Scandinavian phenotype. Such descriptions do not indicate Sub-Saharan African ancestry but rather a within-spectrum diversity of European skin tones.

Moreover, the misunderstanding of terms and the misreading of historical contexts have contributed to the spread of this myth. The term “blár,” for instance, often translated as “black” in modern interpretations, can also mean “blue” or indicate dark colors, including dark hair or clothing, rather than skin color. This linguistic nuance underscores the critical importance of contextual understanding when interpreting historical documents and artifacts.

Final words

The evidence clearly shows that the myth of black Vikings does not match with the findings from history, archaeology, or genetics, showing that such ideas are newer interpretations with no backing from historical documents. The assertion that Vikings were black is often brought up to push current agendas, aiming to undermine the accomplishments of Nordic cultures. However, it is critical to base our understanding of Viking society on accurate historical and scientific findings to ensure that our view of the Viking Age is grounded in reality. The Vikings were not black, and there is no evidence to suggest otherwise.